Ray Dalton never had the chance to get to know his older brother George.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

He was just a toddler when 20-year-old George Dalton packed his kit bag and joined the rest of the Aussie Diggers battling to defend Australia from the advancing Japanese on our northern doorstep.

Ray and his Warrnambool family didn't know it then, nor for a long time after, but within two years, the young Indigenous soldier was dead, a casualty of Australia's worst maritime loss.

July 1 marked 80 years since the Japanese prisoner-of-war ship, the Montevideo Maru, was torpedoed by an American submarine off the coast of the Philippines in 1942, taking all 1053 Australian POWs, including Private George Christopher Dalton, to the bottom of the sea.

The 845 soldiers and 208 civilian males had been captured several months earlier by the Japanese in the fall of Rabaul in New Guinea and were en route to the Japanese-occupied Chinese island of Hainan when the ship was holed.

It wasn't until October 1945, a month after the end of World War II and more than three years after the sinking, that George's family received a telegram notifying them he was 'presumed dead' aboard the Montevideo Maru.

In fact, it took until 2010 for the Australian Government to apologise to the descendants of the victims for the lack of recognition of their deaths. Eight decades on and George Dalton's family says his story and those of all who perished in the tragedy, went untold for too long.

Aboriginal military historian Peter Bakker believes the disaster was unreported by the government during the war for reasons of national morale, already low by 1942 as the conflict in the Pacific drew closer to home.

That the submarine responsible for downing the unmarked, unescorted Japanese POW ship was an Allied sub, the USS Sturgeon, he speculates was also a critical factor in the suppression of details surrounding the incident.

Ray and his nephew, Uncle Locky Eccles, are more determined than ever to keep alive the memories of George and those who died alongside him, suggesting a local commemorative service could be held to mark next year's anniversary of the tragedy.

Midnight Oils lead singer Peter Garrett's grandfather, Labor identity Kim Beazley's uncle and 1939 Prime Minister Sir Earle Page's brother were all among those lost in the disaster.

Coincidentally, another of the victims was not only from Warrnambool, but also shared a surname with George, although unrelated. A non-Indigenous soldier, Bombardier Francis Patrick Dalton served with George in the 2/22nd Battalion. Curiously, both the Dalton lads also had brothers serving in the Pacific.

George's older brother Frank (Francis Daniel) served in New Guinea in the 7th Battalion, returning home unscathed. In what seems to have been a family tradition of service, George and Frank's father Walter served in France in the First World War and did home service as a private with the 17th Garrison in the Second World War.

The unrelated Francis Patrick's younger brother, Private Bernard Joseph Dalton, who also served in the 2/22 Battalion, died tragically in the Tol Plantation Massacre near Rabaul, four months before the Montevideo Maru went down.

Records show the Japanese allowed the prisoners to write home to their families in the months before the sinking. The letters were air-dropped over Port Moresby airport and many were later delivered home to Australia, although none have come to light in Warrnambool.

Inspired by the rallying call to "Get Up! Stand Up! Show Up!" of last week's NAIDOC celebrations, Ray Dalton and Uncle Locky Eccles are keen to shine a light on the life of their brother and uncle, which, like his death, still holds many unanswered questions. Sadly, the circumstances of George's death were rarely spoken of in the Dalton household.

"Nana never talked about it. We were told to keep it quiet because the Americans were involved," Uncle Locky recalls.

Born on June 2, 1920, George was the third of Valentine Margaret, commonly known as 'Ballie' or simply 'Nana', and Walter's 13 children. Brother Ray, now 83, came along in 1938 at the tail end at number 13.

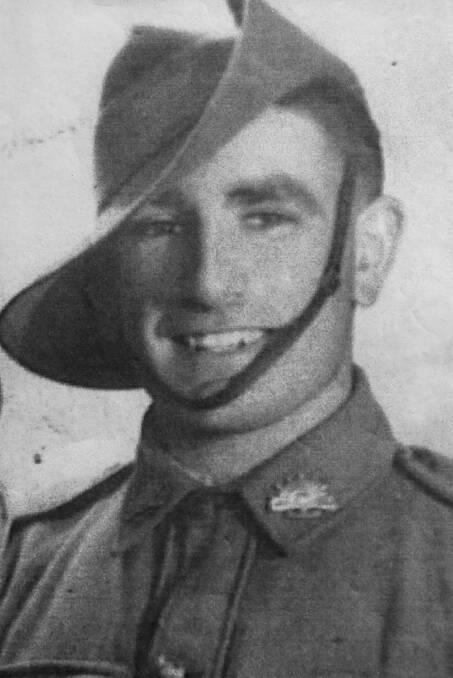

Ray was just two when George enlisted on June 8, 1940, less than a week after turning 20. Among the scant information Ray knows about his big brother is that he was a talented sportsman, a member of the Warrnambool Football Club's premiership side just before the war. There is also a photo of him playing baseball during his Army service.

George gave his occupation as 'labourer' when he enlisted, but just what that work entailed is unknown.

He was also single, but by the time he embarked for Rabaul on April 18, 1941, his papers were amended to show a wife, Mona, nee Drew, as his next of kin. In fact, Ray remembers Mona and the couple's baby daughter living in the family's Merrivale home while George was serving in New Guinea and until the end of the war.

Mona later moved to Melbourne and remarried, returning to Warrnambool to live out her latter years. Not recorded on George's attestation papers was any reference to his Aboriginal heritage.

Ray suspects that like him and Uncle Locky, George was probably unaware of his ancestry, due to his mother's secrecy. Ballie, who not only raised her own 13 children but also her grandson Locky when his home life fell apart as a baby, steadfastly refused to acknowledge her Aboriginality.

"We were brought up as white fellas," explains Uncle Locky, who remembers his grandmother's nightly ritual of rubbing a cut lemon over her face, arms and legs, because, she said, it was good for her skin. In reality, it was a desperate attempt to lighten her skin.

Uncle Locky, now 69, did not suspect his First Nations heritage until age 15 in 1967 when a letter arrived from the government advising that Indigenous residents were to be counted in the Census from that time.

"I remember Nana was cooking something on the stove when I showed her the letter and asked her what it meant," he recounts. "All of a sudden she just picked up the pot and threw it against the wall, she was so angry." Gradually, the clues began to fall into place for the young Locky.

Ray was 18 before he learned the truth about his ancestry from a stranger. He was a handy boxer, undefeated on the local show circuit fighting with Jimmy Sharman and Roy Bell's boxing troupes.

One day he came up against an Aboriginal opponent, eliciting a comment from the crowd that Ray was more Aboriginal than his opponent. It wasn't long before Ray uncovered the secret that his mother had tried so hard to conceal. It was a secret born of fear.

"She brought us up as white because she was afraid of losing us," says Ray. Acknowledging their Aboriginality, she feared, would have increased the chance of them being removed under government policies of the time that created the Stolen Generation.

These days, Ray and Locky, who carries the respected Indigenous honorific of 'Uncle,' are proudly Aboriginal, free to embrace their ancestry in a way that George never had the opportunity to.

At last year's November 1 Aboriginal Remembrance Service in Warrnambool, Uncle Locky spoke publicly for the first time of George's short life and tragic death. It was a small but significant gesture, but one Uncle Locky believes George and his much-loved Nana would have appreciated.

"These people haven't had the recognition they deserve. It's time to get up, stand up and show up," he says.