A piece of Warrnambool's history is about to disappear, but the heroic stories behind its name are set to live on.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

The dramatic recue in 1883 of a two-year-old who had fallen from the breakwater pier into Lady Bay was just one of many sea rescues the Edwards family has been involved in over more than a century.

By next year the 127-year-old Edwards Bridge in South Warrnambool will be gone, the historic bridge no longer able to carry the weight of the growing city's needs.

But its history, and that of the Edwards family in Warrnambool, is almost as old as the city itself. There are calls for the name to be retained when the new look-a-like bridge is built and a plaque erected recognising the history.

The current bridge was built in about 1894, but it wasn't the first bridge to span that spot on the Merri River, according to the Warrnambool and District Historical Society.

In 1863 - the year Warrnambool was declared a borough - the original bridge was built across the Merri River.

Warrnambool wasn't actually declared a town until 1883 - the same year young Roger Edwards saved his little sister from the bottom of Lady Bay.

In 1844, the year before Warrnambool was being planned and surveyed as a town, his father William Robert Edwards was born in England.

It is thought he arrived in Warrnambool sometime in the 1850s or 60s - his marriage certificate in 1868 lists his address as the Warrnambool jetty.

His great, great grand-daughter Gayle Draper said she assumed he may have lived aboard a ship that was moored at one of a number of jetties in Warrnambool's Lady Bay at the time.

William married Ellen Candy, the daughter of a convict who was brought to Tasmania and later made his way to Warrnambool via Melbourne where he'd honed his skills as a carpenter.

William and Ellen had 11 kids and their eldest, Roger, followed in his father's footsteps and became a fisherman.

The teenager made national headlines for the daring rescue of his sister and was awarded a certificate of merit from the Royal Humane Society.

It was a Sunday in late September of 1883, when two-and-a-half-year-old Martha was playing with her siblings and fell from the "breakwater pier".

"All the kids were playing down at the breakwater and she fell in. There was a big swell and it was quite rough and he just ran the length of the jetty and dove in and found her. She was under the water," Gayle said.

"He kept her afloat until the other kids alerted William and he got his boat and rode out and rescued them."

Newspapers reports say she was being rapidly carried into the breakers when the alarm was raised.

"Her brother heard the cries and, throwing his crutch on to the jetty, plunged into the sea near where the little girl had disappeared," newspapers reported.

"He succeeded in bringing her to the surface, and then struggled against the current to keep out of the breakers.

"Beyond the fact of being cripple, he knew he had to combat with the strength of the waves and the current beside the danger arising from sharks."

He had managed to pull the little girl's "almost lifeless body" to the surface after she'd sunk to the bottom under eight feet of water.

Little Martha was unconscious, but was brought around.

But it was the young hero's address at 7 Stanley Street that created the link with the South Warrnambool bridge. "It was always as long as he lived down there it was called Edwards Bridge," Gayle said.

Roger lived there until 1947, Gayle said, information she discovered while researching the family history and accessing census information.

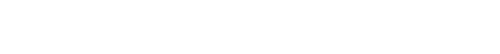

The sandstone property in Stanley Street was converted to a house after it was no longer needed as the location for cutting stone for the breakwater. Most of his relatives lived around the corner in South Warrnambool.

His sister wasn't the only person Roger saved at sea. "He did quite a few rescues. He was in the paper a lot," Gayle said.

In February 1891, he and Edmund Stelling were fishing in Lady Bay when the winds picked up and overturned their boat.

"The perilous position of the two men was observed, but before any attempt could be made to rescue them they were in the breakers struggling for their lives," The Argus reported.

"Edwards succeeded in scrambling to land, but Stelling who could not swim held on to the boat."

Seeing his mate was still in danger, Edwards shedded his excess clothing and dashed back out to help. After several attempts, he reached his mate and helped him to safety.

Roger's son George - Gayle's grandfather - also spent most of his life fishing off the coast of Warrnambool.

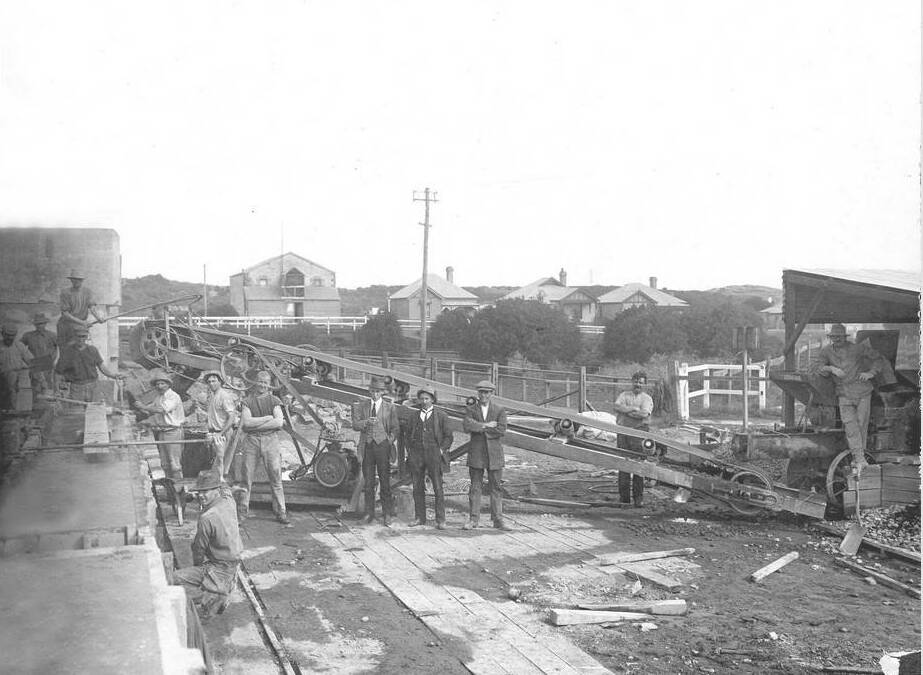

He was born in 1900 and joined the Navy at 15 to fight in WWI where he spent years at seas in the Pacific and Indian oceans aboard the RAN Encounter.

George played in the Navy footy team, and later played alongside Roy Cazaly who has been immortalised in the AFL's unofficial anthem Up there Cazaly.

Gayle's father, Max, followed in the family footsteps and became a fisherman and, like his grandfather before him, was involved in a number of sea rescues.

He was a humble man, Gayle said, and many of those heroic efforts were kept out of the public limelight.

"My brother started fishing at the age of 15 as well. It's in the blood," Gayle said.

Gayle said Max was always "first port of call" for the police if there was ever anyone out to sea in need of help.

"They'd knock on the door at all times of the day or night," she said.

She said he was awarded by the Royal Human Society for going to the rescue of a sunken yacht in heavy seas off Warrnambool.

But his selfless actions were never made public - and that's just the way Max wanted it, Gayle said.

During another daring mission in 1975, his boat was damaged when it was sucked into the side of a ship out at sea when he was attempting to take a doctor and nurse out to an injured seaman.

Max was lucky to be alive himself after his 40-foot shark boat hit rocks during a foggy morning off Apollo Bay in the 1950s, sinking within three minutes.

"Although there was a heavy roll, we had to jump for our lives and take, a chance in the sea," Max told the papers at the time.

Edwards' idea of throwing the four-gallon drums for the shark lines overboard saved their lives, it was reported. They could not have remained afloat in the, heavy surf without them.

"They were very lucky," Gayle said.