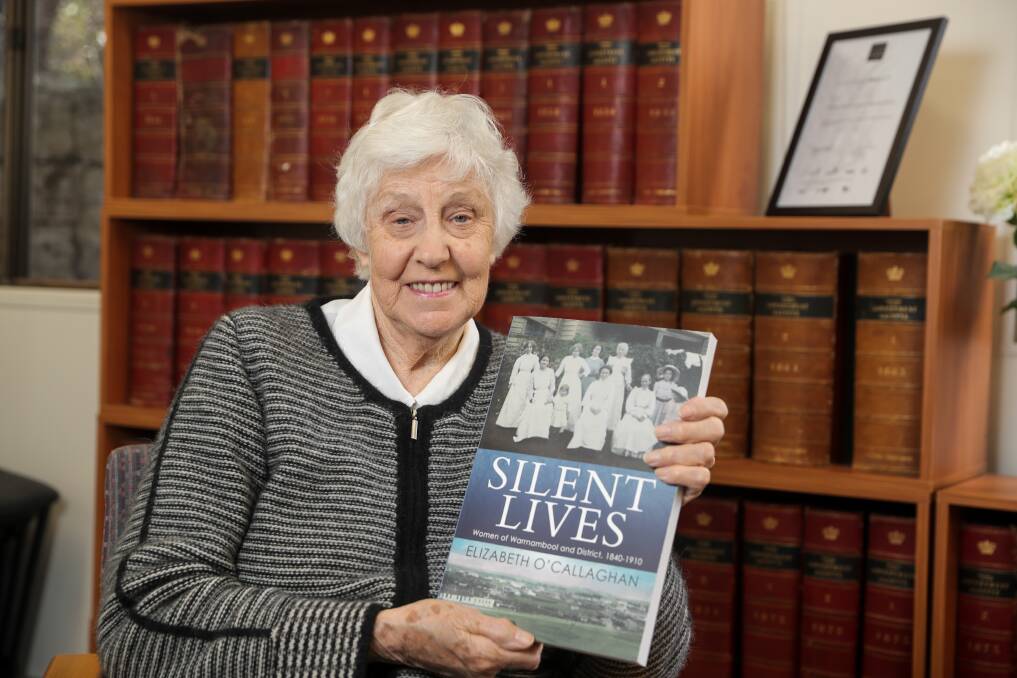

Historian Elizabeth O'Callaghan often sees Warrnambool through the lens of the 19th century. Her new book brings to life the stories of Warrnambool's pioneering women.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Driving the streets of Warrnambool is like taking a journey back through time for Warrnambool historian Elizabeth O’Callaghan.

The stories of those who have long since passed from this world often flood to her mind, especially if they lived in the 19th century.

“Sometimes I think I live too much in the past,” Mrs O’Callaghan said.

A drive to the breakwater will remind her of the elderly seamstress Mary Murphy who was killed in 1888 on the tramway tracks when she didn’t hear the horses coming because she was profoundly deaf.

That story, along with those of about 500 women in Warrnambool’s early history, feature in Mrs O’Callaghan’s book Silent Lives which was officially launched on Thursday.

It is her 50th publication about an aspect of Warrnambool’s history. Previous books on the Warrnambool Exhibition of 1886-87 (“the biggest thing ever held in Warrnambool”), the Flagstaff Hill lighthouses and early trips between Warrnambool and the Otways, are virtually sold out.

She has also written 44 booklets, some of which have won her the Prahran Mechanics Institute local history writing award for small publications.

When it comes to the Warrnambool and District Historical Society collection, there’s not much that Mrs O’Callaghan doesn’t know.

She has spent countless hours cataloging and preserving documents, photos and books.

“I do know the entire collection...and I’m trying to pass that on,” the 84-year-old said.

Mrs O’Callaghan started her research into Warrnambool’s past after she retired as principal of Derrinallum Secondary College in 1991 and moved here.

Born in Colac, she later moved to Melbourne with her parents and four brothers after her father enlisted in 1940 when she was just seven.

Life was hard for her mother who had to raise five children, three of them younger than Elizabeth, while her father was serving in New Guinea.

“My father was a man of his time. He was a man of great vision with all the things he thought of but I was initially a great disappointment, didn’t marry and all that,” she said.

However, Mrs O’Callaghan gained three university degrees and taught in primary and secondary schools across Victoria and in England.

During the school holidays, her travels took her all over the world – sometimes as a tour guide.

But, she said, being a tour guide in North Africa in the 1970s was not safe for a woman.

On one trip her bus driver was arrested for hitting the chief of police in Tangiers and breaking his teeth. “He had to pay 2000 pounds damage. It was just a way to get money out of tourists,” she said.

“We were just told to get the hell out of the place.”

For Mrs O’Callaghan, travelling was not about the food and restaurants. It was the museums, castles, art galleries and old houses, not so much what was in them but the history behind them.

It was Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum’s history that made Mrs O’Callaghan choose Warrnambool to retire, that and the fact it was close to her property on the Great Ocean Road near the Twelve Apostles.

She became a volunteer at Flagstaff Hill and began taking guided tours – sometimes as many as eight a day.

“At that time I had met and married Les O’Callaghan who was the leading historian in the town and had been for 30 years,” she said.

“Les was 96 when he died. I was 15 years younger, so it was a bit amazing for everybody.

“I started to get interested in the history. Les lived history.

“He had been here since the 1930s and he’d walked the streets as a young boy and had known everybody - who lived where, what happened here.”

Mrs O’Callaghan’s knowledge of all things Warrnambool past came from Les as well as the years they spent preserving and cataloging Warrnambool’s historical collection. “I like things to be organised,” she said.

During that work she uncovered many of the stories for Silent Lives, which brings the lives of Warrnambool’s women out from the shadows of the men who dominate the city’s history.

“I’ve always been interested in the women because they do not feature in history. Our history, in any country really, is a history of the men,” Mrs O’Callaghan said.

“It completely excludes women. You can expunge people from history very easily.”

Birth notices of the day would never name the mothers. Theatre programs would list the names of its male stars, but women were simply listed as ‘lady amateurs’.

“You’ve got to dig and find these women,” Mrs O’Callaghan said.

“In my book I’m trying to bring them out of the house, which most of them weren’t.”

The cover of Silent Lives features a picture of women from the late 1880s, but Mrs O’Callaghan doesn’t know who they are. “They’re unknown women. They’re silent lives,” she said.

She hopes someone who picks up her book will recognise them and solve the mystery.

The region’s Aboriginal women are also given a voice in the book.

“We always talk about the dislocation of the Aboriginal men, but the women suffered more than anyone else,” she said. “There was nothing for them whatsoever because they had no household to keep and no food to gather because the sheep had eaten all the stuff they used to gather.”

The stories of 19th century women who were forced to have backyard abortions or abandon their babies on the steps of pubs or at people’s doors are also told.

With newspapers of the 1800s covering court cases in great detail, the lives of those less fortunate have left a bigger mark on history than those who may have achived great things.

“If I’m driving over the Hopkins River bridge sometimes I think of Sophia Charlesworth,” Mrs O’Callaghan said.

“She was in court dozens of times. She was an alcoholic and in the end she went across the bridge to the hotel and was refused a drink.

I’ve always been interested in the women because they do not feature in history. Our history, in any country really, is a history of the men

- Warrnambool historian Elizabeth O'Callaghan

“She takes her bonnet off, carefully ties the ribbons of the bonnet on the railing and then jumps.

“Such a sad life.”

She was jailed a number of times in Portland and when released Sophia would have to walk back to Warrnambool. During one period of incarceration one of her children, who was just six months old, died.

“Everytime I drive in Henna Street I think of the house on the corner of Timor Street called Jenolan.

“Henrietta Price and her husband married in their mid-30s after having known each other when they were young (and were rumoured to be engaged) and then met again and got married.

“The only time she ever went out of Victoria was on her honeymoon when they went to the Blue Mountains and Jenolan Caves. They came back and built a house and named it that.”

In 1902 when she suffered appendicitis, the operation was carried out on the kitchen table of her parents’ house at 94 Merri Street. It was said to be one of the first operations of its kind in Warrnambool.

“Then I see Tay House in Henna Street and think of the girl boarders at Hohenlohe College lining up on a Saturday morning for their daily dose of castor oil,” Mrs O’Callaghan said.

Hohenlohe College was one of the best-known 19th century private school for girls. It was founded in 1893 by Agnes Easson – who had spent six years as the resident governess for the family of German Prince Hohenlohe – and her sister Helen.

Not all women lived silent lives. The 1891 Women’s Sufferage Petition which called for women to have equal rights as men to vote contained the signature of many Warrnambool women.

“Per head of population, more women in Warrnambool signed the petition than in any other Victorian town,” she said.

In 1897, three women publicly protested when they turned up to a Warrnambool polling booth and asked for ballot papers. They were refused.

Hardship was the norm for the region’s pioneering women. Eliza Hornsby, a midwife who lived at Nullawarre, knew this more than most.

With no doctor for 22 miles, she would travel the sometimes impassable roads to help the women give birth in primitive conditions.

“Eliza Hornsby, who toiled so long and hard for other mothers, had 12 children herself but, sadly, only five of them reached adulthood.”

Death of children in Warrnambool and district were so common that they often went unrecorded.

For one Prudence Selby, who arrived in Australia with two healthy boys, she suffered much tragedy with seven pregnancies yielding no living children.

Her last child, a son, breathed for just a few hours. A few months later she died after a fall from a horse at age 41.

For more than a century the accomplishments of women in sport, education, business, the arts and charity work have gone unrecognised, but Silent Lives finally gives them a voice.

With so much of Warrnambool’s history to still be told, Mrs O’Callaghan is working on her next booklet about Warrnambool and the Boer War.