Why on earth would you do Ice?

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Crystal methamphetamine hydrochloride is a filthy drug.

It is made in toilet bowls. It is mixed in filthy buckets. It is peddled at street level by the worst people in our society.

It can be smoked, injected and snorted.

It is highly addictive, can cause stroke, memory loss, anorexia, heart problems and sleep problems.

It can make you look years older than you are, damage your teeth and cause disgusting skin lesions.

It is highly addictive, causes hallucinations and paranoia. Users often become aggressive and violent.

Why on earth would you do Ice?

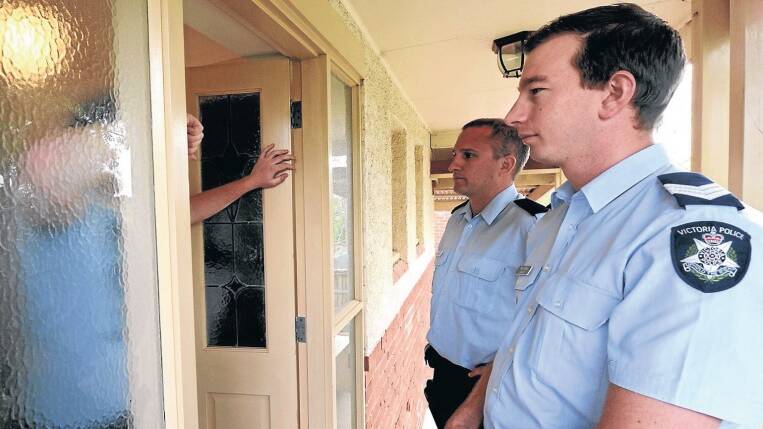

The thin blue line

Police say they are doing their best to combat the ice scourge, but admit they need help.

Police across Australia have called it a "whole of community" problem, but on occasion they're still not getting support of the community.

In Victoria, a parliamentary committee reporting on ice largely ignored a top cop who called for a swathe of legislative changes to tighten the screws on drug traffickers and users.

Acting Chief Commissioner Graham Ashton said police would benefit from several legislative amendments that would make it harder for alleged offenders to beat drugs charges, and give police the chance to charge more people with ice offences, in the force's submission to the Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee.

Mr Ashton said being able to charge offenders with drug trafficking based on the weight of the substance, rather than having to rely on other evidence of trafficking, would remove a common defence that the offender had the drugs for personal use.

Mr Ashton said it should also be mandatory for sellers of chemical glassware and equipment to provide police with the buyer's End-User Declaration, which contains their identification. Some retailers already provide police with this information on a voluntary basis.

None of these proposals were mentioned in the 54 recommendations made by the committee.

In NSW, police Commissioner Andrew Scipione said last month the ice menace was now so large there should be a national approach to tackle it.

He spoke about the issue being 'world-wide' and said nothing short of a national taskforce or summit would be appropriate to address the growing scourge.

"Clearly we need to do all we can. We owe it to our communities, we owe it to our families, our friends and if that's what it takes then we probably should consider it."

The penalties

- VIC - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract a fine of $500,000 and/or life imprisonment.

- NSW - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract a fine of $550,000 and/or life imprisonment.

- SA - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract a fine of $500,000 and/or life imprisonment.

- TAS - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract 21 years imprisonment.

- WA - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract 25 years imprisonment.

- ACT -Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract life imprisonment.

- QLD - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract 25 years imprisonment.

- NT - Trafficking a large commercial quantity can attract life imprisonment.

The global fight

US and Western Europe

The BBC report that according to the UN, methamphetamine - a term which includes the drug as a powder and its stronger and more addictive crystal form - was used by one million people in the US in 2011.

The US is not alone in its experiences. In the Czech Republic, where it is known as Pervitin, it's a more serious problem than heroin, while in Greece a cheap and dangerous variant called sisa reportedly sells for two euros a hit.

But in the UK, crystal meth is currently used less than almost every other drug according to the BBC.

Asia

The TImes of India reports that while meth has long been a scourge across east and southeast Asia, staff at the rehab centre in India's Mumbai's Masina Hospital say it only surfaced as a concern in the city in the past 18 to 24 months.

India is home to one of the world's biggest chemical industries and is a major source of key meth ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which are both legally used in medication such as decongestants.

Along with China, India is the most commonly cited origin of illicit shipments of these precursor drugs destined for meth labs abroad, particularly in neighbouring Myanmar but as far afield as central America and Africa, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.

In China, police are making massive raids in a bid to stamp out crystal meth ice and distribution.

In January this year, the LA Times reported that more than 3,000 police officers equipped with helicopters and motorboats and accompanied by dogs descended on a southern Chinese village notorious for making crystal meth, seizing 3 tons of the drug and 23 tons of raw materials and arresting 182 people.

The paper reported that three officers were injured in the operation, including two who were shot and one who was struck by a car.

Even in the reclusive North Korea, ice use is gripping the populace.

The Washington Post reports that a study published in the journal North Korea Review says that parts of North Korea are experiencing a crystal meth "epidemic," with an "upsurge" of recreational meth use and accompanying addiction in the country's northern provinces.

Oceania

In New Zealand and Australia the UN estimates that it is used by about 1% of the population.

Impacts: The traumatized mother

A South Coast NSW mother has spoken of living with the “monster that is ice” and how the drug, widely available in the local area, has affected her family.

The woman, who doesn’t want to be named, has told of the horror of her child becoming addicted to crystal methamphetamine or ice.

Her child was 15, top of their class, involved in Air Cadets and set for a career in the air force.

Then ice hit her family.

“Then they got involved with the wrong crowd, I thought they were a leader but they became a follower. Life went downhill from there,” she said.

“I believe my child started with marijuana but soon progressed to harder stuff like heroin, methamphetamine or ice, crack and even steroids.

“The change was incredible – from a loving, caring child to being aggressive towards themselves and the people who loved them.

“Life is hell, not only for the addict, but their family as well.

“To all parents – never give up on your children – it is the ice not the child. Just try and get them help."

- South coast NSW mother of an ice addict

“I’ve had furniture thrown at me. I’ve been beaten by ice, not my child, sworn at, called names. There were fights with their father.

“My child is no angel. I know they have done wrong but ice has been the perpetrator for most of it.

The mother said a stigma attached to drug taking made it hard to get support.

“We tried everything. No one seemed to give a s… because it was drugs.

“I have had no child in my life for four years – I’ve had ice in my life.”

She spoke of a life where the child would party for days on end and then sleep for days to recover.

During that time they would often be coming down off the drug but would then go off to another party and the cycle would start all over again.

“I used to say they were sleeping their life away but they were actually killing themselves,” she said.

“To all parents – never give up on your children – it is the ice not the child. Just try and get them help."

Impacts: Losing dad's money

Steve* and his father were "the best of mates".

When his beloved dad died three years ago, he gave his son a wealthy inheritance to help him and his young family.

Steve will never forgive himself for what he did next.

A drug addict for almost 25 years, he blew the lot - more than $50,000 - on ice.

"My dad was everything to me," Steve says.

"How am I ever meant to deal with what I did ... I can't."

Now clean of the drug for almost six months, Steve remains at a healing centre in regional Victoria where he is trying desperately to control his drinking.

"I'm off the drugs and I'll never go back ... but I drink that much because I can't deal with what ice did to my life," he says.

"I hate myself for what I did with dad's money. I hate myself for what I did to my family, my kids ... I hate myself so much."

Steve had been a drug user since the tender age of 14, when he was quickly swallowed up in the rave party scene.

At that time he was using drugs like ecstasy, speed and cocaine, or as he puts it, "anything".

"I hate myself for what I did with dad's money."

- Steve - Victorian ice user

It was at 16 that he began injecting speed, or methamphetamine, a drug similar to ice, but not as strong.

A qualified builder and chef, Steve has managed for most of his life to hold down a job and support his family.

That was until a few years ago.

"It may all start out as fun and games ... but you watch, it (ice) will ruin your life," he says.

"It destroyed mine."

It was a cruel encounter in 2007 which introduced Steve to his first taste of ice.

Emerging clean of drugs after three months in rehabilitation, the father-of-two was handed a small bag of white crystals from another man undergoing rehab.

In that bag was about $100 worth of ice.

"And then it hit the fan ... looking back that's the moment when my already drug-fuelled life went to a whole new nasty level," he says.

"It was just nuts, my life was quickly ruined. I was starting to slowly go insane, everything just went haywire and I was pretty much using it (ice) to feel better in myself."

"My already drug-fuelled life went to a whole new nasty level."

- Steve - Victorian ice user

After injecting the drug, Steve said it was normal to go seven days without sleep or food ... the whole time using.

"I hate to say it, but most of the time I was on a building site I was off my head," he says.

*Steve is not his real name.

Impacts: The front line

Police and paramedics are usually the first to encounter a violent or uncontrollable ice user.

South Coast NSW paramedic Kerry Joseph will never forget the night it took three police officers to hold her patient down despite him being strapped to a stretcher in the back of an ambulance.

“He was a teenager, not a large boy, but he was out of control, with the strength of an ox,” the paramedic of 22 years said.

The young man had taken the drug ice and was smashing his way through his parents’ home when Ms Joseph arrived with the police.

“It took about 40 minutes to control him,” Ms Joseph said.

“His temperature was through the roof. He was frying by the time we got him to hospital.

“That’s one of the things ice does, it cooks them. Their temperature spikes, they fit and they face multiple-organ failure.

“It is a horrible way to die,” she said.

Ms Joseph said the boy was from a seemingly "normal" family.

“His parents were worried sick, they had no idea he had tried ice.

“It was horribly confronting for them to witness their son in this state."

“That’s one of the things ice does, it cooks them. Their temperature spikes, they fit and they face multiple-organ failure."

- Paramedic Kerry Joseph

Impacts: Starting young

Children as young as 10 are abusing ice.

The startling revelation comes from local doctors and drug treatment organisations, who say kids who haven't yet finished primary school are seeking treatment for addictions to the now widespread drug.

Ballarat Health Services' Youth Mental Health Services department and Ballarat Community Health confirmed children in the Victorian city had been seeking withdrawal treatment and help for mental illnesses caused by ice.

They also say the drug doesn't discriminate, with children from both private and public schools using.

BHS Youth Mental Health Services consultant psychiatrist Dr Ravi Srinivasaraju and clinical manager Dr Julie Rowse said young people needed to be aware that only one use of the drug could result in the automatic onset of mental illness.

"There have been very young children, some only 10-years-old, who have presented here due to ice," Dr Rowse said.

"Not everybody who uses substances like ice go on to develop a mental illness, however, ice has been known to have effects, such as drug induced psychosis, immediately."

Ballarat Community Health chief executive officer Robyn Reeves said her organisation had also seen young children seeking treatment for ice use.

"We have certainly had some very young clients using ice and, unfortunately, it will probably continue to get younger," Ms Reeves said.

Impacts: The footy coach

IN his 12 years as a coach, Brendan Broadbent has seen his fair share of substance abuse in football clubs.

While plenty of players have experimented with alcohol, marijuana and amphetamines, it’s the rise of crystal methamphetamine that has Broadbent shining a light on an issue usually dealt with in-house.

“In the past three to four years I’ve been involved in coaching, there has been a small element of young men who try this particular type of drug,” Broadbent said.

“It is a particularly strong substance that does have a greater effect on the person than perhaps what some other substances have had in the past.

“Everyone has a few beers after the game, or even marijuana, but the impact of those substances on the individual’s performance is not particularly seen.

“With ice, the impact is definitely seen.”

Broadbent said one of the most obvious indicators of ice use on the football field was lacklustre performance.

“When people use ice their fitness levels are dramatically affected,” he said.

“You also see a change in the way they communicate with their team-mates. They become a little bit segregated and their commitment and attitude towards the sport that they started out loving drops away a lot.”

Broadbent said in his experience, people turned to drugs for a combination of reasons, including poor self-esteem, pressure of expectations, desire to experiment and falling in with the wrong crowd.

“I’m talking predominantly about football because that’s the area I’ve coached,” he said.

“It’s made up of predominantly young males, guys who seem to be bulletproof, coming into that 18 to 25 age group.

“They’re the type of people who will experiment. If that particular substance is available to them and it’s in front of them, they’re bound to try it.”

The Horsham coach said it was important clubs around the country were aware of what was happening to their playing group.

“If people want to stick their heads in the sand and think it’s not happening here, then they are well and truly going to be left behind when all of a sudden it does impact their club.”

Impacts: The indigenous effect

Raelene Stephens, nurse unit manager of the Mildura District Aboriginal Service's alcohol and other drugs program says ice use has reached epidemic proportions over the past two years, with children as young as 12 being exposed to the drug.

She says dealers have been targeting Aboriginal youths who have an income through jobs in food or hospitality. They are sold large amounts of ice in the knowledge they will rack up large debts. "Then they come after the families for payment," Stephens says.

Victoria's new Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Youth, Andrew Jackomos, warned in July that ice use was reaching a crisis point. He says various Koori groups comprising senior indigenous community leaders want the Napthine government to convene a forum.

"People are frustrated that they can't do anything … They don't know where to turn to. Ice is a huge problem in our community," Jackomos told Fairfax Media in July.

It is not just Koori groups looking for leadership from Spring Street: communities right across Victoria want a whole-of-government approach to dealing with the ice problem.

Impacts: Family violence

EXPERTS and victims have warned the scourge of ice addiction in regional areas is having a direct impact on the rise and severity of family violence.

Child and Family Services has recorded an increase in the number of cases where ice is involved.

CAFS Family Violence Intervention program co-ordinator Bob Maika said ice may not be the root cause of family violence incidents but it was increasingly reported and contributed to the severity of attacks.

“It certainly is present in a lot of the work we do. Certainly we are working with more men that are presenting with issues of ice abuse,” Mr Maika said.

“Ice is like any drug of dependence. While it is a complexity added to family violence, like alcohol and marijuana, it doesn’t cause the family the violence – but it is a contributing factor.”

One victim of domestic violence told Fairfax Media the severity of one attack when her partner was under the influence of drugs turned him into a “deranged monster”.

“He was completely out of control,” she said.

“The brutality of that attack was on another level; that attack landed me in hospital begging for help.

“I knew that night if I didn’t accept what was happening, I would not see the next morning and, you see, I have four children to think of.”

What is ice?

Crystal methamphetamine hydrochloride has a high risk of dependence and its use carries a range of consequences, including brain and mental health conditions, heart and lung problems, paranoia, increased risk of stroke and chronic memory loss.

The drug releases monoamines and can eventually destroy the brain's receptors, leading to a point where the user cannot feel pleasure without further ice use.

Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs chief executive Jann Smith said people who injected ice were also at a high risk of contracting a blood borne disease, such as HIV or hepatitis.

She said anecdotal evidence showed that Tasmania was experiencing the same as what much of regional Australia was already going through, with police and member groups of the council confirming ice use was on the increase.

Ms Smith said it created particular challenges in small communities.

``In any small community, the impact will be broadly felt,'' Ms Smith said.

The community push back

On the NSW and Victorian border at Mildura, community groups have made sure awareness of the growing problem of the drug “ice” doesn’t dissolve.

Red Cliffs and Irymple Lions clubs have donated $400 towards re-printing the Project Ice Mildura banner to be placed on the back of the Sunraysia Bus Lines number 11 bus.

Sunraysia Bus Lines then stepped up and offered to foot the cost of the banner on display for the next six months.

Project Ice Mildura focuses on drug education, prevention and treatment strategies and involves government and non-government agencies and stakeholders.

Project Ice co-ordinator Rebecca Alderton said there had been about 80 Project Ice information sessions since they started in October, with the program reaching about 3000 people across the region.

“It’s just fantastic they have supported the program and shows the community support that’s alive in this region,” Ms Alderton said.