The Woman in the Library by Sulari Gentill. Ultimo Press. 288pp. $32.99.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

The Woman In the Library is a standalone novel by Batlow-based author Sulari Gentill, best known for her Rowland Sinclair series set in the 1930s.

In this latest offering, Gentill sets out to satirise the tropes of both crime and postmodernism in a tricksy, metafictional way, but the novel's main conceit of unreliable narration falls flat.

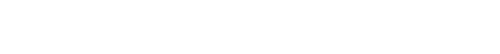

The plot initially centres on the discovery of a woman's body in the Boston Public Library. But the reader soon realises this is a story within a story; the murder at the library actually belongs to the plot of a (fictional) novel written by an Australian writer called Hannah Tigone. Tigone is effectively Gentill's protagonist, but she is absent throughout, visible only through the chapters that masquerade as the plot of Gentill's novel.

Interspersed with these chapters are emails to Tigone from Leo, an American who is fact-checking the story for her on the ground in Boston.

Lines between fact and fiction become further blurred when a character called Leo pops up in Tigone's story, and Tigone receives a letter from the police suggesting the real Leo has committed a crime.

Over recent years a handful of British writers have written metafictional crime novels to great effect. Among these are Janice Hallett's The Twyford Code and Stuart Turton's The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle.

Both are told innovative ways that spoof Enid Blyton's Famous Five series and the country house murder plot, respectively. Similarly, Jo Baker's The Body Lies is a masterful example of the metafictional format, centring on a professor of creative writing whose experiences are uncannily captured in a draft novel produced by one of her students.

But these novels also demonstrate that layers of self-referential sub-plots are not a substitute for an actual story.

In The Woman In The Library, we have neither story nor style.

The old-school humour that works in the Rowland Sinclair novels is dull and tedious when transplanted into a contemporary setting, and Leo's metafictional commentary is cringeworthy rather than clever.

As the four protagonists only become acquainted at the time the murder is committed, it is hard to believe they share a meaningful bond.

Consequently, when the culprit is revealed after some very contrived twists and turns, I felt that nothing had ever been at stake.

Ultimately, Gentill's appropriation of the metafictional format is cynical rather than satirical, falling back on empty cliches masquerading as tired philosophical questions.