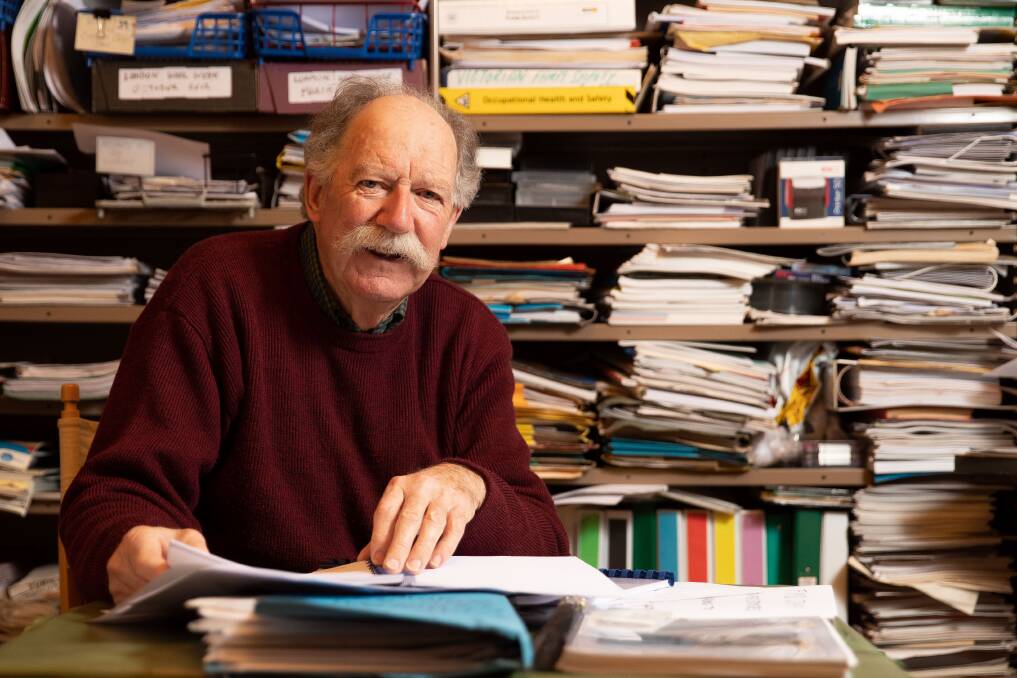

After having his stock quarantined in the 1980s, Hamilton farmer Michael Blake has a "fire in his belly" to make sure producers are properly compensated if there is a foot and mouth outbreak.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Mr Blake is urging farmers to get a valuation on their livestock as a matter of priority to ensure they don't miss out if there is an outbreak.

A United Nations trip to Nepal to inspect farms riddled with foot and mouth in 2016 also inspired him to speak out in a bid to help other farmers.

Quarantined in the '80s

"My fire in my belly goes back to 1984 when Bally Glunin Park was put into compulsory quarantine and disposal of all stock," Mr Blake said.

Authorities had detected Brucellosis - also called contagious abortion - in his cattle, some of which were Scottish Highland Galloway.

"I fought very, very hard because I knew it was an incorrect diagnosis," Mr Blake said.

"They didn't do the proper protocols in the first instance, and the science behind what they had suggested was wrong. In the end I won the fight."

But it took an emotion toll. "It was a very stressful time," Mr Blake said.

"For our family it was a terrible stress because my father was a great cattle man and it just broke his pride."

While he faced the prospect of losing all his stock, he said that over the 16 months the department spent trying to prove its case they slaughtered 12 cattle.

Living through that experience has made him more aware of how he should prepare should foot and mouth reach our shores.

Be prepared for compo claim

Mr Blake said the compensation scheme now was far better and fairer than what it was back then when there was just one price for stock.

From that "learning experience" he wants to help farmers facing a potential foot and mouth outbreak to help themselves.

He said there were few things that farmers could be proactive about in preparing for an outbreak but the most important was valuation and compensation.

Mr Blake recommends having a recognised person provide a commercial value of stock which will help ensure compensation is paid at the farm gate price.

My fire in my belly goes back to 1984 when Bally Glunin Park was put into compulsory quarantine and disposal of all stock.

- Michael Blake

He also suggested getting an accredited valuation not just on all livestock but wool, fodder, fencing equipment and buildings that livestock might be in contact with.

"If all these things are done, when it comes to slaughter it will be very hard to suggest otherwise that that's their value," he said.

"If you don't have this document and if there is a disaster then basically the animals at the point of slaughter ... with foot and mouth, they have no value and that's what you get paid."

Mr Blake said farmers might be ineligible for compensation if they didn't report a suspected emergency animal disease, or report it quick enough.

FMD first-hand experience

Mr Blake said he did not want to be a scaremonger about foot and mouth disease, but his first-hand experience in Nepal in 2017 had made him very much aware of its impact on farmers.

"I saw what it does in Nepal," he said.

The trip, under the auspices of the United Nation, was to provide real-life training and the team took precautions with all their belongings to make sure they didn't bring FMD back to Australia.

Mr Blake took three sets of clothes to Nepal on that trip, some he kept in a plastic bag to prevent contamination.

"When we went out into the field we were fully encased in hazchem to the extent that double gloved...chem suits, gumboots," Mr Blake said.

The hazardous chemical suits were tied with gaffa tape to the gumboots and gloves, and glasses and masks were worn.

"Each night all these clothes were washed in citric acid, we were given special sachets," Mr Blake said.

On the day of departure, most people washed what they called their "field clothes" and put them in a charity box at the front of the hotel.

"They were still sanitised but the risk was still there if you didn't quite wash it properly," he said.

"I put my razor, my hairbrush and my toothbrush in the rubbish because when you're working with foot and mouth contact is through saliva, touching and air. Your lungs and your nostrils can carry it for up to seven days."

To lower the risk of bringing anything back to his own farm, when Mr Blake arrived in Australia he "quarantined" in Perth before he returned to Hamilton.

Have a biosecurity plan

Mr Blake has had a biosecurity plan for Bally Glunin Park since 2001 when a foot and mouth outbreak hit the UK. In 2008 he received the biosecurity farmer of Australia award.

"And the protocols have been pretty tight," he said.

With foot and mouth so close to Australian shores "you can row a boat across", Mr Blake said his confidence would return when he saw the disease start to move north-west away from Australia.

Mr Blake said the emphasis for returned overseas travellers had rightly been on footwear.

"These animals are basically too sacred. They just walked the streets... if you're not watching you'll pick it up and transmit it," he said.

How compo works

State Agriculture Minister Gayle Tierney said compensation was front of mind.

The Member for Western Province said that under the Emergency Animal Disease Response Agreement the costs of an outbreak such as foot and mouth disease would be shared between governments and industry groups.

"The government would be responsible for 80 per cent of the response costs and the relevant industries would be be responsible for 20 per cent," Ms Tierney said.

"The Commonwealth initially pays, essentially underwrites, industry's share of the costs and industry group pays the loan through levies over a period of up to 10 years."

$10m mobile roll out

The state government has announced it will roll out new portable sample testing and mobile incident centres as part of a $10 million package to bolster the response to any emergency animal disease outbreak.

If an outbreak occurs, a portable testing lab will be deployed to outbreak locations to allow real-time on-site sample testing.

The mobile incident command centres and IT system upgrades would allow for tracking of outbreaks and coordination of online permits for livestock movements.

Agriculture Victoria chief veterinary officer Dr Graeme Cooke said biosecurity plans were extremely important.

He said foot-and-mouth disease and lumpy skin disease were major threats to Victoria's agriculture.

"This is the most infectious livestock disease. It moves very, very quickly," he said.

"That is why we are investing in a range of capabilities should Victoria ever need to deal with these challenging diseases."

An additional 49 dedicated emergency animal disease staff were also being recruited to advance response measures already under way.